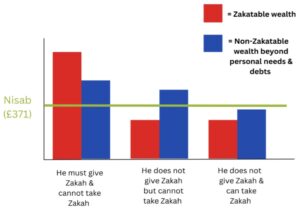

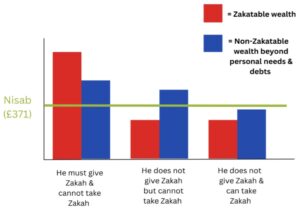

Can I give Zakāh to someone who is in debt and How do I decide if they are a worthy recepient?

Question: Who can Zakāh be given to and how

Download the pdf here:

Maʿālim Irshādiyyah li Ṣināʿati Ṭālib al-ʿIlm – Guideposts for the Development of a Seeker of Islamic Knowledge

By Shaykh ʿAwwāmah, (Riyad: Dārul Minhāj, 2013) – Hardback Cover – 490 pages

Shaykh Muhammad ʿAwwāmah is one of the leading scholars of ḥadīth today. A meticulous researcher who has dedicated his entire life to the field of ḥadīth. Works that he has researched include: (1) Musnad ʿUmar ibn ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz (2) Naṣb al-Rāyah (3) Taqrīb al-Tahdhīb (4) Muṣannaf Ibn Abī Shaybah (5) Sunan Abī Dāwūd (6) Al-Qawl al-Badīʿ fi’l-Ṣalāti ʿAla’l Ḥabīb al-Shafīʿ (7) Al-Kāshif (8) Majālis fī Tafsīr Qawlihi Taʿālā (9) Al-Ansāb (from the letter Shīn to the end of the letter ʿAyn) (10) Al-Shamā’il al-Muḥammadiyyah.

His authored works include: (1) Athar al-Ḥadīth al-Sharīf (2) Adab al-Ikhtilāf (3) Al-Mukhtār Min Farā’id al-Nuqūl (4) Ḥujjiyah Afʿāl al-Rasūl (5) Min Ṣiḥāḥ al-Aḥādīth al-Qudusiyyah (6) Dirāsah Ḥadīthiyyah Muqārānah (7) Maʿālim Irshādiyyah

Note: references for quotes have been omitted from this article as they may be found in the book.

Shaykh Muhammad ʿAwwamah’s Maʿālim Irshādiyyah li Ṣināʿati Ṭālib al-ʿIlm (معالم إرشادية لصناعة طالب العلم) is a must for any seeker of Islamic knowledge looking for guidance and inspiration in the long and arduous journey of seeking Islamic knowledge or any teacher of Islamic knowledge looking for the tools to inspire his students. It is hoped that by following the advices presented by the author, a seeker of Islamic knowledge shall attain their objective of acquiring Islamic knowledge coupled with the inspiration to act upon their knowledge, and a teacher will find the means to assist the students of Islamic knowledge in acquiring their objective.

A Cursory Glance at the Book

The book is divided into four sections:

I shall now present snippets of what is mentioned under each section.

Introduction to Islamic knowledge, virtues of Islamic knowledge, virtues of the gatherings of Islamic knowledge, and virtues of the scholars of Islamic knowledge

After elucidating upon the meaning and qualities of Islamic knowledge and the importance for a seeker of knowledge to adopt the methodology of the scholars of the past, the author explains some of the virtues of Islamic knowledge, the virtues of the gatherings of Islamic knowledge, and the virtues of the scholars of Islamic knowledge.

The author explains that it was through the Islamic knowledge given to him by Allah the Almighty that Sayyidunā Ādam ʿalayh al-salām gained the respect of the angels, such that they were commanded to prostrate before him. He then demonstrates how scholars such as Ibn ʿAbd al-Barr raḥimahullah (d.463 AH) have recorded from the ṣaḥābah that seeking Islamic knowledge is equivalent to striving in the path of Allah. After this, he explains the meaning of the oft quoted ḥadῑth of the Prophet ṣallallāhu ʿalayhi wasallam:

طلبُ العلمِ فريضةٌ على كلِّ مسلمٍ

The seeking of knowledge is an obligation upon every Muslim.

The author then continues to demonstrate the virtues of the gatherings in which Islamic knowledge is discussed by proving that gatherings in which Islamic knowledge is discussed are more virtuous than secluding oneself for worship. After this, the author dedicates some eight pages or so towards the virtues of the scholars of Islamic knowledge. He explains that the effect of the scholars upon this nation is similar to the effect of the Prophets and Messengers upon their nations; this is because the scholars are the inheritors of the Prophet. Similarly, the Qur’ān has utilised the word ‘ʿUlamā’ for the Prophets. Allah the Almighty says:

شهد الله أنّه لا إله إلّا هو والملائكة وأولو العلم قائما بالقسط

Allah witnesses that there is no deity except Him, as do the angels and the people of Islamic knowledge (the Prophets), standing with justice.

Based upon this, Ibn Rajab al-Ḥanbalῑ raḥimahullah (d.795 AH) writes:

وكفى بهذا شرفًا للعلماء أنّهم يُسمَّون باسمٍ يجتمعون هم والأنبياءُ فيه

And this is a sufficient honour for the scholars of Islamic knowledge that they have been given a name that they share with the Prophets.

The Shaykh then mentions the importance of acting upon the knowledge that one has gained. He concludes with a discussion pertaining to the effect that Islamic knowledge has upon the scholars themselves.

Guideposts for a student of Islamic knowledge

In his introduction to the various guideposts that have been stationed for a student of knowledge, Shaykh ʿAwwāmah presents myriad quotes from the pious predecessors. Through quotes from luminaries the likes of Imām Muḥammad ibn al-Ḥasan raḥimahullah (d.189 AH) and Imām al-Shāfiʿῑ raḥimahullah (d.204 AH), Shaykh ʿAwwāmah demonstrates the differing views of the scholars with regards to the innate traits that are to be found in a student of knowledge. For example, the statement of Imām al-Māwardῑ raḥimahullah (d.450 AH) is presented, who said:

الشّروط الّتي يتوفّر بها علم الطّالب وينتهي معها كمال الرّاغب – مع ما يلاحظ به من التّوفيق ويمدّ به من المعونة – فتسعة شروط …:

The conditions through which the knowledge of a seeker becomes complete and through which a seeker may attain distinction – along with considering divine inspiration and the assistance gained through it – are nine…

The Shaykh then presents the nine conditions mentioned by Imām al-Māwardῑ raḥimahullah (d.450 AH):

Shaykh ʿAwwamah also presents the statements of Imām Muḥammad ibn al-Ḥasan raḥimahullah (d.189 AH) and Imām al-Shāfiʿῑ raḥimahullah (d.204 AH), both of whom, interestingly, stressed the importance of intellect and understanding within a student of knowledge. A pertinent incident involving Ibn Shubrumah raḥimahullah (d.144 AH) is also presented. When a man asked him a question, he gave the answer, however, the man did not understand, Ibn Shubrumah raḥimahullah (d.144 AH) repeated the answer, again, the man did not understand, Ibn Shubrumah raḥimahullah (d.144 AH) then said:

إنْ كُنتَ لم تفهم لأنّك لم تفهم فستَفْهم بالإعادة وإن كنتَ لم تفهم لأنّك لاَ تَفْهم فهذا داءٌ لا دواءَ له

If you have not understood it because you have not understood it, then you shall understand it when it is repeated, and if you have not understood because you do not have an understanding, then this is an illness for which there is no cure.

A study of the book reveals that Shaykh has designated fifteen guideposts that a seeker of Islamic knowledge should follow in order to attain his objective:

1) To have sincerity in intention

2) To recognise the lofty status of a seeker of Islamic knowledge

3) To have intellect

The Shaykh explains that there are two types of intellect:

Natural: this is the intellect embedded within an individual

Acquired: this is the intellect acquired after years of life experience

The Shaykh explains that one who is blessed with both types of intellect is capable of great wonders. While the Shaykh explains that a teacher should value a student who has natural intellect, he also explains that a teacher should bear patience with a student who does not have a high natural intellect. Indeed, such students may develop an acquired intellect and may even surpass those who have a natural intellect. He then presents a thought-provoking story as testimony for this; in his biography upon Al-Rabῑʿ ibn Sulaymān raḥimahullah (d.256 AH), Taqῑ al-Dῑn al-Subkῑ raḥimahullah (d.756 AH) quotes Al-Qaffāl raḥimahullah who said in his fatāwā:

كان الرّبيع بطيءَ الفهمِ فكرّر الشافعيُّ عليه مسألةً واحدةً أربعين مرّةً فلَمْ يفهم وقام من المجلس حياءً فدعاه الشّافعيّ في خلوةٍ وكرّر عليه حتّى فَهِم!

Al-Rabῑʿ was a slow-paced learner, so [Imām] al-Shāfiʿī would repeat a single mas’alah to him fourty times, but he would still not understand it, he (Al-Rabīʿ) would then stand and leave the gathering out of embarrassment, [Imām] al-Shāfiʿī would then call him (Al-Rabīʿ) privately and would continue repeating the mas’alah to him until he would understand it!

Shaykh ʿAwwāmah comments upon this story:

ورضي الله عن الإمام الشافعيّ في صبرِه وتحمّلِه وفي ذوقِه وأدبِه وتلطّفِه مع من يرجوْ خيرَه وقد جاء قبل هذا الخبر بسطرين أنّ الشّافعيَّ قال له ما أحبَّك إليّ! وقال ما خَدَمَنِيْ أحدٌ قطّ ما خدمني الرّبيع بن سليمان وقال له يوما يا ربيع لو أمكنني أن أُطْعِمَك العلم لأَطْعَمْتُكَ فليكن الإمام الشافعيّ قدوةَ كلّ أستاذ ومعلّم

May Allah be pleased with Imām al-Shāfiʿῑ for his patience, forbearance, attitude, conduct and affection with someone for whom he hoped goodness, and it is mentioned [in Ṭabqāt al-Shāfiʿiyyah al-Kubrā of Tāj al-Dῑn al-Subkῑ in the biography of Al-Rabīʿ ibn Sulaymān two lines before the above-mentioned] that [Imām] al-Shāfiʿῑ said to him, “I have so much love for you!” and he (Imām al-Shāfiʿī) said, “Nobody has provided me with a service like the service provided to me by Al-Rabῑʿ ibn Sulayman,” and he once said to him, “Oh Rabīʿ, if it were possible for me to feed you Islamic knowledge, I would feed it to you.” Hence, every teacher and guide should make Imām al-Shāfiʿī their example.

4) To valorise time and to have a zeal for attaining Islamic knowledge

The Shaykh quotes the statement of the great Imām, Fakhr al-Dῑn al-Rāzῑ raḥimahullah (d.606 AH), who said:

والله إنّني أتأسّف في الفوات عن الاشتغال بالعلم في وقت الأكل فإنّ الوقت والزّمان عزيز

I swear by Allah, I regret the opportunity I have lost of engrossing in Islamic knowledge due to the need to eat food, for indeed, time and age are precious.

From amongst the incidents presented as an example of the zeal for acquiring Islamic knowledge, perhaps the most pertinent incident is the incident of Ibn Abῑ Ḥātim al-Rāzῑ raḥimahullah (d.327 AH). Ibn Abῑ Ḥātim raḥimahullah (d.327 AH) writes in Al-Jarḥ wa’l-Taʿdīl, in the biography of ʿUqbah ibn ʿAbd al-Ghāfir al-Azdῑ raḥimahullah:

سألت أبي وهو في النّزع عن عقبة بن عبد الغافر هل له صحبة؟ فقال لا بلسان مسكين

I asked my father while he was in the pangs of death regarding ʿUqbah ibn ʿAbd al-Ghāfir that did he gain the companionship [of the Prophet ṣallallāhu ʿalayhi wasallam]? He replied, “No,” in a low tone.

5) To have courage in acquiring Islamic knowledge

Shaykh highlights the importance of developing courage in preparation for the hardships that one shall face in acquiring this Islamic knowledge. He dedicates an entire sub-section highlighting the oft-quoted phrase:

لا يستطاع العلم براحة الجسد

Islamic knowledge cannot be sought with bodily comfort.

Imam Muslim has narrated this phrase from Imām Yāḥyā ibn Abī Kathīr raḥimahullah (d.132 AH) in his Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, though the narration itself is not ḥadīth of the Prophet ṣallallāhu ʿalayhi wasallam and the narration does not fall within the conditions of his book.

6) To free oneself from all distractions

Shaykh ʿAwwāmah quotes the amazing statement of Imām Abū Aḥmad Naṣr ibn Aḥmad raḥimahullah, who said:

لا ينال هذا العلم إلّا من عطّل دكّانه وخرّب بستانه وهجر إخوانه ومات أقرب أهله إليه فلم يشهد جنازته

This Islamic knowledge cannot be attained except by one who abandons his shop, destroys his garden, leaves his friends, and his closest relative (e.g. parents or children) pass away and he is unable to attend their funeral (due to being engrossed in studies).

7) To develop a correct companionship

In demonstrating the importance of choosing a correct companion, Shaykh ʿAwwāmah mentions that a human being is easily influenced by other human beings. The proof of this, he writes, is the ḥadīth of the Prophet ṣallallāhu ʿalayhi wasallam wherein the Prophet ṣallallāhu ʿalayhi wasallam said:

والفخر والخيلاء في أهل الخيل والإبل الفدّادين أهل الوبر والسّكينة في أهل الغنم

Arrogance and haughtiness is in the owners of horses and camels, who are rude and uncivil, and tranquillity is found with the owners of goats.

The ḥadīth shows that the nature of a human being is even influenced by animals; accordingly, the influence of other fellow human beings would be greater.

8) To attain knowledge from recognised teachers i.e. Mashāyikh

Shaykh ʿAwwāmah mentions that the scholars of the past did not pay attention to an individual who had not studied under a teacher, nor did they consider such a person to have a value, and nor did they allow him to have a say in matters of religion. Shaykh then presents the narration of Imām al-Bayhaqī raḥimahullah (d.458 AH) who narrates in his Al-Madkhal that Imām al-Awzāʿī raḥimahullah (d.159 AH) said:

ما زال هذا العلم عزيزا يتلقّاه الرّجال حتّى وقع في الصّحف فحمله أو دخل فيه غير أهله

This Islamic knowledge remained venerable, and the men (scholars) continued to benefit from until it was printed onto the papers, and so then it was carried by those who were not worthy of it who also delved into it.

In this chapter, the Shaykh also critiques the methodology of the universities that produce individuals who are half-knowledgeable. He quotes Ḥāfiẓ Ibn Taymiyyah raḥimahullah (d.728 AH) who said:

أكثر ما يفسد الدّنيا نصف متكلّم ونصف متفقّه

That which corrupts the world the most is a half-theologian and a half-scholar.

The Shaykh then explains why a person who is half-knowledgeable – due to having not attained the knowledge from recognised teachers – is of great harm to human beings. He writes:

ذلك أنّ العالم يتكلّم بعلم والجاهل يسكت لأنّه يعرف أنّه جاهل أمّا نصف العالم فيتكلّم ظانّا أنّه عالم وهو جاهل فيضلّ ويضلّ

This is because a scholar of Islamic knowledge speaks with [the] Islamic knowledge [that he possesses] and a layman remains silent as he knows that he is a layman, as for a half-scholar, he speaks thinking that he possesses Islamic knowledge though he is a layman, hence he becomes misguided and misguides others.

In this section, Shaykh ʿAwwāmah also touches upon a critically important point, the negative effects of certain Islamic computer programmes. Shaykh explains that beneficial knowledge with which one experiences prosperity (Barakah) and light (Nūr) in his knowledge can only be attained through the companionship of a qualified teacher. Thus, one cannot become a specialist in ḥadīth until he has specialised in the study of ḥadīth under a qualified teacher.

In addition to what has been mentioned by Shaykh, it is important to add that while computer programmes such as Maktabah al-Shāmilah have a plethora of positives, when used correctly, they undoubtedly have their negatives. With such computer programmes, one could bypass the conventional and traditional methods of research (which involve effort, time, and dedication), resulting in a plethora of mistakes in one’s work that only the learned scholars will recognise. Indeed, the learned scholars are able to easily discern between genuine research (which involves the researcher genuinely studying the books that he is quoting) and counterfeit research that has been compiled by typing in keywords onto a computer programme.

While the scholars of the past would read through an entire book in order to understand the sentiments of a book, today, an ʿĀlim (scholar) – and at times even a layman – simply types in key words into a computer programme and begins to give an impression to the general laymen that his knowledge is incredibly vast. This is not to mention the numerous individuals who get the false impression that with computer programmes such as Maktabah al-Shāmilah, we have more knowledge than the scholars of the past (for a rebuttal of this false impression, see Shaykh’s Athar al-Ḥadīth al-Sharīf, pg.197 onwards). Besides using computer programmes in this incorrect manner, there are of course many benefits to the computer programmes.

9) To choose the correct teacher

Shaykh emphasises the importance of choosing the right teacher. He presents the statement of Ibrāhim al-Nakhaʿī raḥimahullah (d.96 AH) who said:

كانوا إذا أتوا الرّجل ليأخذوا عنه نظروا إلى سمته وإلى صلاته وإلى حاله ثمّ يأخذون عنه

When they (the scholars) would come to a man to take from him [Islamic knowledge], they would look at his physical appearance, his ṣalāh, and his state, then they would take from him.

10) To accompany the teacher for a long period of time

Shaykh laments that in this day and age, the tradition of spending decades in the company of one’s teacher has all but vanished. He mentions that Imām Ibn Ḥibbān raḥimahullah (d.354 AH) has recorded in his Al-Thiqāt (الثقات) that Nuʿaym ibn ʿAbdillah al-Mujmir raḥimahullah (d. ca 120 AH) spent 20 years in the company of Sayyidunā Abū Hurayrah raḍiyallahu ʿanhu. Ḥāfiẓ al-Dhahabī raḥimahullah (d.748 AH) records that Thābit al-Bunānī raḥimahullah (d.123 AH) spent 40 years in the company of Sayyidunā Anas ibn Mālik raḍiyallahu ʿanhu (d.93 AH). Similarly, Nāfiʿ ibn ʿAbdullah raḥimahullah spent 35 to 40 years in the company of Imām Mālik raḥimahullah (d.179 AH).

11) To adorn oneself with the regalia of respect

Shaykh ʿAwwāmah writes that respect towards elders is an innate quality found within animals too. As proof, he presents the verse of the Qur’ān:

حتّى إذا أتوا على واد النّمل قالت نملة يا أيّها النّمل ادخلوا مساكنكم لا يحطمنّكم سليمان وجنوده وهم لا يشعرون

Until, when they came upon the valley of the ants, an ant said, ‘Oh ants enter your dwellings that you are not crushed by Solomon and his soldiers while they are unaware’.

The words ‘while they are unaware’ indicates the respect that the ant had towards the army of Sayyidunā Sulaymān ʿalayh al-salām; the ant excused the army of Sayyidunā Sulaymān ʿalayh al-salām from any blame. If this is the respect an ant had for the companions of Sayyidunā Sulaymān ʿalayh al-salām, one can imagine the respect that we, as seekers of Islamic knowledge, need to have for the companions of the Prophet ṣallallāhu ʿalayhi wasallam and the scholars of the past.

12) To bear patience over the hardships in attaining Islamic knowledge and to avoid truanting

Shaykh quotes Abū Hilāl al-ʿAskarī raḥimahullah (d.395 AH) who relates that Imām Al Karkhī raḥimahullah (d.340 AH) used to come to the lessons of his teacher, Abū Khāzim ʿAbd al-Ḥamīd ibn ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz raḥimahullah (d.292 AH), every day. In fact, Imām al-Karkhī raḥimahullah (d.340 AH) would even attend the venue of the lessons on Friday, a day on which there would be no lesson, he would say:

كنت أحضر مجلس أبي خازم يوم الجمعة بالغداة من غير أن يكون درس لئلَا أنقض عادتي من الحضور

I used to attend the gathering of Abū Khāzim on Friday mornings without there being a lesson, so that I do not lose the habit of attending [the lessons]

13) To go through the subject of the lesson before the lesson and to revise the subject after the lesson

The Shaykh presents the statement of Qādī ʿIyāḍ raḥimahullah (d.544 AH), who wrote in the biography of his teacher, Ghālib ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn ʿAṭiyyah al-Gharnāṭī raḥimahullah (d.518 AH):

أنّه كرّر قراءة “صحيح البخاري” سبع مئة مرّة وقد عمّر ٧٧ عاما فيكون – تقريبا – قد قرأ “الصحيح” في كلّ شهر مرّة على مدار ستّين سنة

That he repeated the recitation of Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī seven-hundred times, and indeed he lived for seventy-seven years, thus he recited the Ṣaḥīḥ approximately once every month for sixty years.

14) To discuss issues of Islamic knowledge with one another (Mudhākarah)

The Shaykh mentions that the most important benefit of this is that it strengthens one’s memory of the knowledge that one possesses and allows one to increase this knowledge by learning from others. The Shaykh presents an incident mentioned by Yaʿqūb ibn Sufyān raḥimahullah (d.277AH) in Al-Maʿrifah wa’l-Tārīkh who narrates from Fuḍayl ibn Ghazwān raḥimahullah (d. ca 141 -149 AH) that he said:

كان ابن شبرمة والمغيرة بن مقسم الضبّي والحارث العكليّ والقعقاع بن يزيد وغيرهم يسمرون بالفقه فربما لم يقوموا إلى النّداء بالفجر

Ibn Shubrumah, Al-Mughīrah ibn Miqsām al-Ḍabbī, Al-Ḥārith al-ʿUklī, Al-Qaʿqāʿ ibn Yazīd, and others would discuss issues of fiqh at night. At times, they would not even get up when the adhān of fajr would be called out (due to the intensity of their discussion).

15) To have the capability to ask the right questions, i.e. to be meticulously inquisitive while maintaining respect and maturity

The Shaykh presents the statement of Al-Zarnūjī raḥimahullah (d.620 AH) who said:

إنّما سمّي طالب العلم “ما تقول” لكثرة ما يقولون في الزّمان الأوّل ما تقولون في هذه المسألة؟

Indeed, a seeker of Islamic knowledge is labelled [with the title] ‘what do you say regarding…’ due to the abundance of them in the earlier times saying, ‘What do you say regarding this issue?’

Guideposts for a teachers of Islamic knowledge in terms of their role as a teacher

A study of the book reveals that the Shaykh has designated fifteen guideposts for teachers of Islamic knowledge to attain their objective:

1) To fulfil the following:

In demonstrating how a teacher should provide his students with courage and hope, the Shaykh presents the story of Ḥasan ibn Ziyād al-Lu’lu’ī raḥimahullah (d.204 AH). When Ḥasan ibn Ziyād al-Lu’lu’ī raḥimahullah (d.204 AH) would not understand a certain aspect of the lesson, his teacher, Imām Abū Yūsuf raḥimahullah (d.182 AH) would say:

أرفق…أنت السّاعة مثلك حين بدأت؟

Take it easy… Are you in the same state that you were when you began?

Ḥasan ibn Ziyād raḥimahullah (d.204 AH) states:

فأقول لا قد وقفت منها على أشياء وإن كنت لم أستتمّ ما أريد

I would say, “No, I have learnt some parts from it, though I have not yet achieved what I wanted to achieve.”

To which Imām Abū Yūsuf raḥimahullah (d.182 AH) would say:

فليس من شيء ينقص إلّا يوشك أن يبلغ غايته اصبر فإنّي أرجو أن تبلغ ما تريد

There is nothing that moves slowly except that it eventually reaches its objective, have patience, for indeed I have hope that you will acquire what you seek.

2) To motivate the students to memorise that which may benefit them academically

Shaykh presents the famous story of Imām al-Ghazālī raḥimahullah (d.505 AH) whose possession were once stolen as he was walking. He immediately began to follow the thief, when the thief warned him, Imām al-Ghazālī raḥimahullah (d.505 AH) pleaded, “Please give me back my book that you have taken, I have travelled far and wide to gain the knowledge needed to write the book,” the thief replied:

كيف تدّعي أنّك عرفت علمها وقد أخذناها منك فتجرّدت عن معرفتها وبقيت بلا علم!

How do you claim that you have knowledge of the book, [because] indeed when we took it from you, your knowledge of it abandoned you and [now] you remain without knowledge!

Imām al-Ghazālī raḥimahullah (d.505 AH) states that this became the lesson he needed to begin memorising books.

3) To embed within them the methodology of learning Islamic knowledge in order of its importance

Shaykh mentions that this guidepost entails three important aspects:

The Shaykh explains that it is not possible for one to reach the roof without a ladder. Thus, a student must climb the ladder of Islamic knowledge gradually, avoiding the desire to expedite this process.

4) To imbue within them the ability to be eloquent and meticulous in speech

Shaykh gives examples of common mistakes in pronunciation and punctuation that occur in general dialogue amongst people. He mentions that a teacher should also ensure that the student learns to pronounce common words in the Arabic language. He then draws the tutor’s attention to the incident of Imām al-Shāfiʿī raḥimahullah (d.204 AH) which shows the attentive nature of Imām al-Shāfiʿī raḥimahullah towards the speech of his student, Imām al-Muzanī raḥimahullah (d.264 AH). Imām al-Muzanī raḥimahullah (d.264 AH) states:

سمعني الشافعيّ يوما وأنا أقول فلان كذّاب فقال لي يا إبراهيم أكس ألفاظك أحسنها لا تقل فلان كذّاب ولكن قل حديثه ليس بشيء

[Imām] al-Shāfiʿī [raḥimahullah] heard me one day utter [the words], “So and so is a liar”, so he said to me, “Oh Ibrahim, discipline your words, and refine them, do not say, ‘So and so is a liar’, say, ‘His narrations are nothing.’”

5) To motivate them to study the deeper meanings of the linguistics of the Qur’ān and ḥadīth in detail

In explaining this, Shaykh gives the example of the ḥadīth of the Prophet ṣallallāhu ʿalayhi wasallam wherein he said:

آتي باب الجنّة يوم القيامة فأستفتح

I shall come to the door of Jannah on the day of Jannah and ask that it be opened.

Here we notice that the Prophet ṣallallāhu ʿalayhi wasallam used the word آتي. Shaykh explains that a student must ponder as to why the supposedly synonymous word جاء has not been used. He explains that a deeper study of the two words would lead to the conclusion that the word آتي involves the meaning of arriving slowly and with care while the word جاء does not deliver this meaning. Hence, the Prophet ṣallallāhu ʿalayhi wasallam shall walk to the gates of Jannah on the Day of Judgement slowly and with care. Shaykh mentions that in this regard, two books should be particularly encouraged: Mufradāt al-Qur’ān (مفردات القرآن) of Al-Rāgib al-Aṣfahānī raḥimahullah (d.502 AH) and Al-Nihāyah (النهاية) of Ibn Al Athīr Raḥimahullah (d.606 AH).

6) To imbue within them the ability to say, “I do not know”

Shaykh quotes the statement of the great tābiʿī, Muḥammad ibn ʿAjlān raḥimahullah (d.148 AH), who said:

إذا أخطأ العالم “لا أدري” أصيبت مقاتله

Once a scholar forgets the words ‘I do not know’, his destruction is inevitable.

Shaykh emphasizes the importance of students refraining from engaging in debates over matters for which their knowledge is insufficient. However, Shaykh also advises that the importance of the words ‘I do not know’ should not be abused such that one uses the statement as a means of avoiding study. He states:

وأمّا قول ياقوت الحمويّ عن “لا أدري وأنّها نصف العلم” إنّه النّصف المرذول

As for the statement of Yāqūt al-Ḥamawī [raḥimahullah] that ‘‘I do not know’ is half of knowledge’, indeed, it is the disgraced half.

7) To pay close attention to the students

Shaykh mentions that this close attention should be maintained even once the student has developed knowledge that makes him incorrectly assume that he is eligible to independently conduct his own lessons. He then presents some interesting stories, starting with a thought-provoking incident that occurred between Imām Abū Ḥanīfah raḥimahullah (d.150 AH) and Imām Abū Yūsuf raḥimahullah (d.182 AH).

8) To develop an ability of academic impartiality within the students

Shaykh mentions that this includes a student inculcating within a student the importance of retracting a view or statement when it is sufficiently proven to be incorrect. He mentions an incident in which Sayyidunā ʿAlī raḍiyallahu ʿanhu was asked a question to which he replied with an answer. The questioner then said:

ليس كذلك يا أمير المؤمنين، ولكن كذا وكذا

It is not like that Oh Leader of the Believers; rather, it is like this and this.

Upon recognizing that the man’s statement is correct, Sayyidunā ʿAlī raḍiyallahu ʿanhu replied:

أصبت وأخطأت وفوق كلّ ذي علم عليم

You have spoken correctly, and I have erred, and above every person of knowledge there is the All-Knowing.

9) To command them to follow the view of the majority and to avoid irregular opinions

Shaykh dedicates a few pages to this discussion. With the rise of modernist views in Islām, this discussion makes a very interesting read. The most pertinent statement mentioned by Shaykh is the statement of Sayyidunā Muʿādh raḍiyallahu ʿanhu who sets the standard for what is to be considered a regular opinion in Sharīʿah and what is to be considered to the contrary. Sayyidunā Muʿādh raḍiyallahu ʿanhu said:

فإنّ على الحقّ نورا

Indeed, Ḥaqq (truth) has a light upon it.

This means that Ḥaqq (truth) – in this context; regular opinion in Sharī’ah – is that for which one gains genuine satisfaction that it is the correct interpretation of the command of Allah. Whereas an irregular opinion has been defined by Sayyidunā Muʿādh raḍiyallahu ʿanhu as one which makes one think or utter:

ما هذه؟!

What is this?!

This means that for an irregular opinion, within the deep crevices of the heart, an individual will know that the opinion could never be a correct interpretation of the command of Allah. Thus, the irregular opinion irks and bothers him; though outwardly people attempt to convince him (or he convinces himself) that it is the correct interpretation of the command of Allah.

10) To imbue within them the wisdom required in order to deal with the laity

Shaykh stresses the importance of educating the students to avoid confusing the masses and to avoid any attempt to sway them away from their understanding of Sharīʿah – as long as their understanding of Sharīʿah has been accommodated by the majority of the scholars of the past. When the caliph at the time of Imām Mālik raḥimahullah (d.179 AH) wanted to enforce the laws found in Al-Muwaṭṭa’, a ḥadīth collection written by Imām Mālik raḥimahullah (d.179 AH), Imām Mālik raḥimahullah (d.179 AH) advised:

فإن ذهبت تحوّلهم ممّا يعرفون إلى ما لا يعرفون رأوا ذلك كفرا، ولكن أقرّ أهل كلّ بلدة على ما فيها من العلم

Thus, if you attempt to change the people from that which they understand to that which they do not understand, they will consider that to be disbelief, rather, maintain each city according to their [respective understanding of] Islamic knowledge.

11) To emphasise that they focus their attention upon that which falls within the boundaries of that which is authentic

Shaykh expands upon this by mentioning that if a scholar mentions fabricated narrations in his speeches, and the layman learns that the narrations quoted are fabricated, he will have no reliance left upon the scholar.

12) To emphasise that they revert to the original sources in all forms of research

In this context, Shaykh also emphasises the importance of taking great precaution and exercising apprehension in rejecting the existence of a narration. He then recollects a few incidents in this regard.

13) To prepare a group from amongst them for issuing fatāwā and to train them in this field

Shaykh ʿAwwāmah stresses and explains the importance of preparing a group of students for the position of issuing fatwā. He praises the institutes of the scholars of the Indian Sub-Continent scholars who have initiated a specific year for specialising in fatwā after six years of study.

14) To emphasise to the students that they recognise the well-being and state of the people around them

Shaykh ʿAwwāmah recounts the incident of Imām Muḥammad raḥimahullah (d.189 AH) that he would visit the traders of his city to understand the different methods of trade; this would then assist him in issuing rulings pertaining to such trades.

15) To imbue within them the ability to critically assess all that they hear or read while maintaining etiquette and tact

Shaykh recounts a personal story in which the Shaykh states that during his early days of study, he read a story that apparently seemed to besmirch the jurisprudential ability of Imām al-Bukhārī raḥimahullah (d.256 AH), the Shaykh, perturbed by the story reverted to his teacher, the illustrious muḥaddith, Shaykh ʿAbdullah Sirāj al-Dīn, who replied:

لا تصدّق كلّ ما تقرأ

Do not believe everything that you read.

Guideposts for a teacher of Islamic knowledge in terms of his role as an educator (Murabbī)

The Shaykh has designated five guideposts for a teacher of Islamic knowledge in terms of his role as an educator (Murabbī):

1) To advise and guide them of the essentials of Islamic character step-by-step

2) To advise them of the etiquettes of knowledge and to encourage them to practice what they have learnt

Shaykh ʿAwwāmah emphasises that practising upon what has been learnt involves two actions:

The Shaykh recounts the story of Imām Mālik raḥimahullah (d.179 AH), who told Imām al-Shāfiʿī raḥimahullah (d.204 AH) when the latter began his study of Al-Muwaṭṭa’:

يا محمّد اتّق الله واجتنب المعاصي فإنّه سيكون لك شأن من الشّأن

Oh Muhammad, fear Allah, and refrain from sinning, for indeed soon you shall have a status.

Imām Mālik raḥimahullah (d.179 AH) then said:

إنّ الله عزّ وجلّ قد ألقى على قلبك نورا فلا تطفئه بالمعصية

Indeed, Allah, the Elevated, the Exalted, has planted light in your heart, so do not extinguish it by committing sin.

3) To give them courage in a practical manner, for example, by electing the students to lead ṣalāh or to deliver a khuṭbah, etc.

The Shaykh records the inspiring story of Imām al-Dāraquṭnī raḥimahullah (d.385 AH) and his student ʿAbd al-Ghanī al-Azdī raḥimahullah that has been recorded by Ḥāfiẓ al-Dhahabī raḥimahullah (d.748 AH). Ḥāfiẓ al-Dhahabī raḥimahullah (d.748 AH) writes:

ابتدأت بعمل كتاب “المؤتلف والمختلف” فقدم علينا الدارقطنيّ فأخذت عنه أشياء كثيرة منه فلمّا فرغت من تصنيفه سألني أن أقرأه عليه ليسمعه منّي فقلت عنك أخذت أكثره! قال لا تقل هكذا فإنّك أخذته مفرّقا وقد أوردته فيه مجموعا وفيه أشياء كثيرة أخذتها من شيوخك قال فقرأته عليه

I began working on the book Al-Mu’talaf wa’l-Mukhtalaf, hence, when Al-Dāraquṭnī came to visit us, I took a lot from him, then when I completed writing the book, he (Al-Dāraquṭnī) asked that I read the book to him so that he may hear it from me, I said to him, “I have taken the majority of it from you!” He (Al-Dāraquṭnī) replied, “Do not say that for indeed you took it from me in portions, and indeed, you have amalgamated it in this book, and there are many things in it that you have taken from your [other] teachers,” so I read the book to him.

4) To emphasise that they read the biographies of the scholars of the past

Shaykh ʿAwwāmah particularly advises students to study the following two books:

The Shaykh presents an abridged version of a story related by Ibn Abī Ḥātim raḥimahullah (d.327 AH) with regards to Qabīsah ibn ʿUqbah al-Suwa’ī’ raḥimahullah (d.215 AH). Once, a man from the family of the Abbasid caliph came to Qabīsah raḥimahullah (d.215 AH) and requested that he conduct a special gathering of Ḥadīth for him. Qabīsah raḥimahullah (d.215 AH) replied, “Rather, you should join the [usual] gathering with the people”. The man from the Abbasid family threatened, “Do you not recognise a right for the Banū Hāshim?” Immediately, Qabīsah raḥimahullah (d.215 AH) stood up, went into his house, took out a small piece of bread with salt on it, and said:

من رضي من الدّنيا بهذا يهون عليه كلامك!

Your statement means nothing to a man who is content with only this from the world.

These are only snippets from the outstanding book that is Maʿālim Irshādiyyah li Ṣināʿati Ṭālib al-ʿIlm. It is perhaps important to state that on page 301, the Shaykh writes that any individual who wishes to begin the journey of seeking Islamic knowledge should first read Al-Shamā’il al-Muḥammadiyyah to imbue within himself the character and morals of the great paragon of Allah, Prophet Muḥammad ṣallallāhu ʿalayhi wasallam, who was the deliverer of this immensely sacred Islamic knowledge.

Some Salient Features of Maʿālim Irshādiyyah li Ṣināʿati Ṭālib al-ʿIlm

It is evident by looking at the plethora of books that he references, that Shaykh ʿAwwāmah has harnessed the sentiments of other books written in this field, including and not limited to:

Along with gathering the sentiments of these books, the Shaykh presents verses of the Qur’ān, aḥādīth, and multitudes of anecdotes from the lives of the scholars of the past for each of the points that he makes. His main sources for the anecdotes that he has compiled are books that have compiled the biographies of the scholars of the past. These sources include:

Along with this, the Shaykh regularly presents personal experiences and stories of his teachers. Throughout the book, he informs the reader and potential seeker of Islamic knowledge of various personal advices that are of immense benefit. One of the interesting features of the book is Shaykh ʿAwwāmah’s footnotes. Every other page of the book contains a footnote of benefit. At times, Shaykh recounts a past experience or incident of his life, while on other occasions, he provides rulings for certain aḥādīth quoted in the corpus of the work. At times, there are general points of benefit, for example, on page 62, Shaykh ʿAwwāmah presents a poem composed by Imām al-Ḥaramayn al-Juwaynῑ raḥimahullah (d.478 AH). In the footnotes, the Shaykh mentions that the poem has also been attributed to Imām al-Shāfiʿῑ raḥimahullah. He then issues a beneficial statement that is of importance to all students who have an interest in Arabic poetry:

فالشّعر المنحول لعليّ بن أبي طالب والشّافعيّ رضي الله عنهما أكثر من الصّحيح عنهما

There are more poems spuriously attributed to ‘Alῑ ibn Abῑ Ṭālib and [Imām] al-Shāfiʿῑ, May Allah be pleased with both of them, than there are poems authentically established from them.

I humbly urge and emphasise to every scholar, teacher, and student of Islamic knowledge to read this book. I pray to Allah the Almighty that He grants the author of this book, Shaykh Muhammad ʿAwwāmah, the best of rewards, and may He make us from amongst the true seekers of Islamic knowledge, and may He grant us Islamic knowledge that is instrumental to our salvation.

Ameen

Question: Who can Zakāh be given to and how

Question: Someone is visiting London (from another country) for

Question: If a woman gets her period at the

Question: Are WHOOP bands permissible in Ihraam? Answer: In

Question: I ordered some magnesium gummies, I checked the

Download the pdf here: Question: What is the ruling